Table of Contents for Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii)

Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii) is a herbaceous perennial that is native and rare to the central midwestern United States. This plant is a host to the Queen (Danaus gilippus) and Monarch (Danaus plexippus) butterflies. Growing from 1 to 3 feet tall, this species has greenish-white to yellow flowers that bloom from May to July. This plant is federally rare and not in cultivation by gardeners.

Taxonomy and Naming of Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii)

Taxonomy

Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii) was originally named and described by John Torrey, an American botanist. However, the description was invalidly published. The description was published correctly by Asa Gray, another American botanist, in 1856. This species has kept the same name to the present time and is a member of the Dogbane Family (Apocynaceae).

Meaning of the Scientific and Common Names

Scientific Name

The genus name, Asclepias, is named for the Greek god of healing, Asklepios (Flora of Wisconsin). The species name, meadii, is a Latinized version of the last name of the first collector.

Common Name and Alternative Names

The common name of the plant comes from the name of the original collector, Dr. Samuel Barnum Mead (Betz 1989).

Physical Description of Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii)

Description

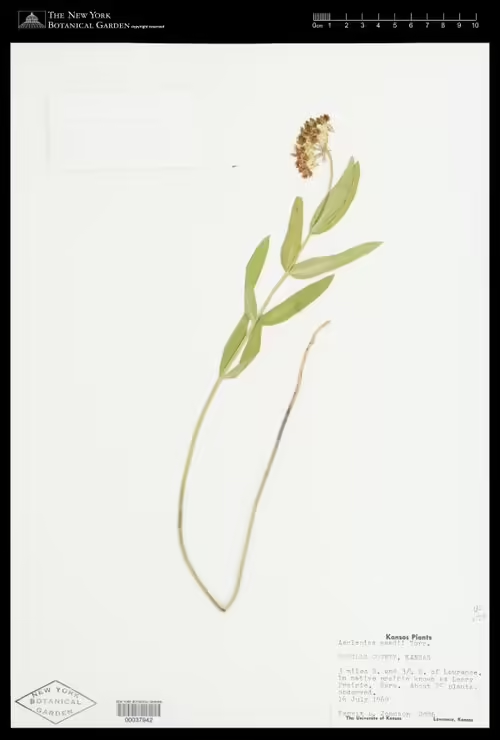

- Plant Type: This plant is a herbaceous perennial.

- Height: 1 to 3 feet

- Stem: The stem is generally simple, but can be branched (Betz 1989) and is glaucous (white). The plant sprouts via a rhizome.

- Leaves: The leaves are opposite, sessile, simple, and lanceolate to ovate in shape and clasping the stem. The leaves are 1 to 3 inches long and 0.4 to 2 inches wide (Woodson 1954).

- Flower color: greenish-white to yellow with purple hoods

- Blooming period: This plant blooms from June to July.

- Fruiting type and period: This plant has follicles that mature in the late summer and fall.

Range of Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii) in the United States and Canada

This milkweed species is native and rare (federally endangered) to the central mid-western United States. This species is listed as being present in Indiana (Kartesz 2015), but may be extirpated from the state (Yatskievych 1995).

Habitat

This species grows in tallgrass prairies that have fire ecology, hay meadows, and barrens (USFWS) and right-of-ways (MO Department of Conservation). It is declining in number due to loss of the virgin prairie habitat it requires (Betz 1989). In 1852, this plant was listed as not being rare on dry rolling prairies in Wisconsin and Minnesota (Parry and Owen 1852), but by 1880 it had already become rare (Greene 1880).

Hosted Insects

This species is a host for the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus), the Queen Butterfly (Danaus gilippus), though apparently only rarely (Betz 1989). It also hosts the unexpected cycnia moth (Cycnia inopinatus) (Roels 2011).

Other Supported Wildlife

This species is a nectar source to bees, especially miner bees and smaller bumblebees (Bowles, et al 1998).

Frequently Asked Questions about Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii)

Is this plant poisonous?

Like other milkweeds, it has cardiac glycosides (cardenolides) and is considered to be poisonous with ingestion.

Does this plant have any ethnobotanical uses?

The Native American Ethobotanical Database does not specifically mention this plant, but milkweeds in general have been used as foods, pharmaceuticals, and fibers.

How is this plant distinguished from other milkweeds?

This milkweed can be identified from other milkweeds in North America by the nodding umbels, as no other milkweed has this (Betz 1989).

Is this plant invasive?

This plant is federally endangered and is not considered to be invasive and has a hard time reproducing because very few of the pods mature.

What caused this plant to become rare?

This milkweed used to be common in the native prairies of the United States. However, settlement of the plains changed the natural fire ecology and native prairies were changed to agricultural fields (Betz 1989 and Bowles, et al 1998). Development and conversion of other lands also reduced the bee populations that are important to pollinate this species. Herbivory by other insects and browsing by deer may also contribute to the decline of this species (Roels 2011). Mowing of prairies for hay also contribute to the reduction (Bowles, et al. 1998). Restoration efforts are on-going at remaining prairies to try to increase the numbers of this plant and there has been some success in Illinois (Taylor, et al. 2009).

Gardening with Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii)

A special note about this plant

This milkweed is not in cultivation and is currently federally endangered because of loss of habitat and reduction of the bee populations. The best to help this plant help in restoring native prairies in order to provide a place for this plant to live and increase its numbers. Consider getting involved with a group such as a land trust or conservancy that help promote the preservation of prairie habitats. If you have a prairie on your property, try to restore the natural fire ecology and do not mow to allow plants such as Mead’s Milkweed a place to thrive.

Optimal Conditions

This species grows best in places where it can receive full sun and a natural prairie ecology with occasional fires.

References

- Betz, Robert F. 1989. Ecology of Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii Torrey). Proceedings of the Eleventh North American Prairie Conference 1989.

- Bowles, M.L., J.L. McBride, and R.F. Betz. 1998. Management and Restoration Ecology of The Federal Threatened Mead’s Milkweed, Asclepias meadii (Asclepiadaceae). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 85: 110-125.

- Greene, Edward Lee. 1880. Notes on Certain Silkweeds. Botanical Gazette 5: 64.

- Parry, C.C. and David Dale Owen. 1852. Systematic catalogue of plants of Wisconsin and Minnesota. (Philadelphia: Lippincott). p. 617.

- Roels, Steven Michael. 2011. Not Easy Being Mead’s: Comparative Herbivory on Three Milkweeds, Including Threatened Mead’s Milkweed (Asclepias meadii), and Seedling Ecology of Mead’s Milkweed. University og Kansas Masters Thesis.

- Taylor, Christopher Alan, John B. Taft, and Charles Warwick. 2009. Canaries in the catbird seat: the past, present, and future of biological resources in a changing environment. (Champaign, IL: Illinois Natural History Survey No. 30).

- Woodson, Robert E. 1954. The North American Species of Asclepias L. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 41: 1-211.

- Yatskievych, Kay. 1995. The Milkweed Family in Indiana. Indiana Native Plant and Wildflower Society News. 2 (2): 1.